UITableView and UICollectionView are workhorses of iOS development, but they demand significant boilerplate. That boilerplate often ends up in view controllers, bloating them unnecessarily.

A common solution is extracting UITableViewDataSource into a dedicated class:

public final class ArrayTableViewDataSource<T>: NSObject, UITableViewDataSource {

private weak var tableView: UITableView?

private let cellFactory: (UITableView, IndexPath, T) -> UITableViewCell

private var items: [T] = []

public init(_ tableView: UITableView, cellFactory: @escaping (UITableView, IndexPath, T) -> UITableViewCell) {

self.tableView = tableView

self.cellFactory = cellFactory

}

public func update(with items: [T]) {

self.items = items

self.tableView?.reloadData()

}

public func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, numberOfRowsInSection section: Int) -> Int {

return items.count

}

public func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, cellForRowAt indexPath: IndexPath) -> UITableViewCell {

return cellFactory(tableView, indexPath, items[indexPath.row])

}

}

class MyViewController: UIViewController {

private lazy var dataSource = ArrayTableViewDataSource<Item>(self.tableView) { tableView, indexPath, item in

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: "Cell", for: indexPath)

cell.setup(with: item)

return cell

}

}This is cleaner—the data source is testable and reusable. Just provide a cellFactory closure to dequeue and configure cells.

But what happens when you need multiple cell types?

The problem: heterogeneous cells

Say you have three data types, each requiring a different cell:

struct Type1 {

let title: String

}

final class CellType1: UITableViewCell {

func setup(with: Type1) { }

}

struct Type2 {

let title: String

let detail: String

}

final class CellType2: UITableViewCell {

func setup(with: Type2) { }

}

struct Type3 {

let title: String

let detail: String

let subtitle: String

}

final class CellType3: UITableViewCell {

func setup(with: Type3) { }

}Approach 1: Using Any

class MyViewController: UIViewController {

private let tableView = UITableView()

private lazy var dataSource = ArrayTableViewDataSource<Any>(self.tableView) { tableView, indexPath, item in

if let item = item as? Type1 {

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: "Cell1", for: indexPath) as! CellType1

cell.setup(with: item)

return cell

}

if let item = item as? Type2 {

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: "Cell2", for: indexPath) as! CellType2

cell.setup(with: item)

return cell

}

if let item = item as? Type3 {

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: "Cell3", for: indexPath) as! CellType3

cell.setup(with: item)

return cell

}

assertionFailure("Did not handle item of type \(type(of: item))")

return UITableViewCell()

}

}Problems:

- The

cellFactorygrows linearly with cell types - Relies on duck typing for dispatch

- No compile-time guarantee that all types are handled

Approach 2: Enum with associated values

enum CellItem {

case item1(Type1)

case item2(Type2)

case item3(Type3)

}

class MyViewController: UIViewController {

private let tableView = UITableView()

private lazy var dataSource = ArrayTableViewDataSource<CellItem>(self.tableView) { tableView, indexPath, cellItem in

switch cellItem {

case let .item1(item):

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: "Cell1", for: indexPath) as! CellType1

cell.setup(with: item)

return cell

case let .item2(item):

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: "Cell2", for: indexPath) as! CellType2

cell.setup(with: item)

return cell

case let .item3(item):

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: "Cell3", for: indexPath) as! CellType3

cell.setup(with: item)

return cell

}

}

}Better—we get exhaustiveness checking. But:

- The

cellFactoryis still bloated - Every screen with different cell combinations needs its own enum

- Violates the Open-Closed Principle: adding a cell type means modifying every usage site

Both approaches also force you to expose cell internals publicly just to populate them.

A better approach: self-rendering components

What if each item knew how to render itself and which cell type it belongs to?

A component needs:

- A reuse identifier

- The ability to register its cell type

- Access to the cell instance for rendering

protocol Component {

associatedtype Cell: UITableViewCell

var reuseID: String { get }

func register(in tableView: UITableView)

func render(in cell: Cell)

}

extension Component {

var reuseID: String {

return String(reflecting: Cell.self)

}

}We can provide default register(in:) implementations for programmatic and nib-based cells:

protocol NibLoadable {

static var nib: UINib { get }

}

extension Component {

func register(in tableView: UITableView) {

tableView.register(Cell.self, forCellReuseIdentifier: reuseID)

}

}

extension Component where Cell: NibLoadable {

func register(in tableView: UITableView) {

tableView.register(Cell.nib, forCellReuseIdentifier: reuseID)

}

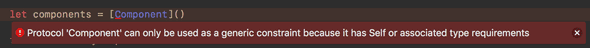

}The PAT problem

Component has an associated type, so we can’t create [Component].

The solution: type erasure.

final class AnyComponent {

private let _register: (UITableView) -> Void

private let _render: (UITableViewCell) -> Void

let reuseID: String

init<Base: Component>(_ base: Base) {

self.reuseID = base.reuseID

self._register = base.register

self._render = { cell in

guard let cell = cell as? Base.Cell else {

assertionFailure("Type mismatch")

return

}

base.render(in: cell)

}

}

func register(in tableView: UITableView) {

_register(tableView)

}

func render(in cell: UITableViewCell) {

_render(cell)

}

}

extension Component {

var anyComponent: AnyComponent {

return AnyComponent(self)

}

}Now the data source simplifies—no more cellFactory:

final class ArrayTableViewDataSource: NSObject, UITableViewDataSource {

private var items: [AnyComponent] = []

private weak var tableView: UITableView?

init(items: [AnyComponent] = [], tableView: UITableView) {

self.items = items

self.tableView = tableView

}

func update(with items: [AnyComponent]) {

self.items = items

self.tableView?.reloadData()

}

func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, numberOfRowsInSection section: Int) -> Int {

return items.count

}

func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, cellForRowAt indexPath: IndexPath) -> UITableViewCell {

let item = items[indexPath.row]

guard let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: item.reuseID) else {

item.register(in: tableView)

return self.tableView(tableView, cellForRowAt: indexPath)

}

item.render(in: cell)

return cell

}

}Usage:

class ViewController: UIViewController {

private lazy var dataSource = ArrayTableViewDataSource(tableView: tableView)

private func showData() {

dataSource.update(with: [

Title(title: "Title").anyComponent,

TitleDetails(title: "Title", details: "Details").anyComponent

])

}

}Cleaner syntax with custom operators

The .anyComponent calls are noisy. A custom operator can help:

precedencegroup ComponentConcatenationPrecedence {

associativity: left

higherThan: AdditionPrecedence

}

infix operator |-+: ComponentConcatenationPrecedence

public struct Form {

let components: [AnyComponent]

static var empty: Form {

return Form(components: [])

}

}

public func |-+ <C: Component>(form: Form, component: C) -> Form {

return Form(components: form.components + [component.anyComponent])

}Now:

class ViewController: UIViewController {

private let tableView = UITableView()

private lazy var dataSource = ArrayTableViewDataSource(tableView: tableView)

private func showData() {

let form = [

"Hello World!",

"Olá Mundo!",

"Bonjour le monde",

"Hola Mundo",

"Hallo Welt"

].reduce(Form.empty) { $0 |-+ Title(title: $1) }

dataSource.render(form)

}

}Conclusion

ArrayTableViewDataSourcebecomes self-sufficient—no external configuration needed- Each

Componentencapsulates its own rendering logic - Adding new cell types means adding new components—no existing code changes required (Open-Closed Principle)

- Components enable consistent, reusable UI building blocks across your app

P.S.

This pattern evolved into Bento, which we built at Babylon Health.